To many of us, when we hear the word photography, we imagine our useful little digital cameras, carefully tucked away in our carry-on and destined for capturing a hike up the canyon or a vacation in Hawaii. (Sounds like a plan, doesn’t it?) In our days of pointing, shooting, and digitally enhancing our images, it’s hard to believe the extensive chemical process that photography once demanded.

Photography debuted on the scene in 1839 thanks to Frenchman, Louis J. M. Daguerre and Englishman, Henry Fox Talbot. Daguerre had been experimenting for years with his partner, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, and, after Niépce’s death, developed a process to create an early photograph or daguerreotype. Every daguerreotype proved unique and appeared on a sheet of copper that is plated with silver and highly polished. The plate is treated with iodine vapors to make it light-sensitive and exposed in a box-like camera that seems reminiscent of a camera obscura. Development in warmed mercury fumes occurs next, and the plate is later “fixed” with salt water. The use of mercury vapors aided the speed of the photographic process which had originally taken eight hours. Daguerre’s use of chemicals took twenty minutes to a half an hour. (I know, it seems like a long time compared with our point and shoot.) For more information on Daguerre and his early photographic process, refer to: www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dagu/hd_dagu.htm/

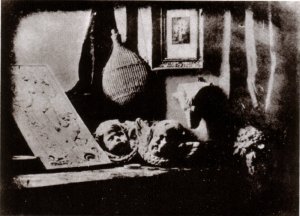

The calotype process also appeared in 1839 thanks to William Henry Fox Talbot. This process proved important to the development of photography because it allowed several prints. Basically, Talbot’s method created negative images once objects were placed on light-sensitive paper and exposed to light. Positive images were created with a second sheet that brought out the first images. This permitted multiple prints or the idea of negatives for further use. See www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tlbt/hd_tlbt.htm for more information.

Many visual artists and art critics were angered and perplexed. They felt all their hard work in fooling the eye and in creating a window on the world seemed superfluous with the introduction of this new medium. From their perspective, photography could never reach the lofty heights of painting, sculpture, or engraving because a camera and chemical processes were involved, not the physical processes of the artist.

In fact, it took years for photographers to gain recognition. Photographs were never exhibited in the same fashion as paintings. Only twenty years later did a photography exhibition appear alongside a painting exhibition in Paris at the Universal Exposition of 1859. Yet, equality still seemed like a distant future, since the two shows were separated in distinct spaces.

NADAR (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon), Eugène Delacroix, ca. 1855. Modern print from original negative in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Photography did, however, offer a relatively inexpensive medium to the increasingly powerful middle class. Some artists, namely Eugène Delacroix, a famous 19th-century French painter, embraced the new medium. Delacroix utilized photography to influence his painting skills and even posed for a photo himself. He often worked from photographs of nude models to save them the time of posing. The artist also liked to examine how photographs can be imbued with greater emotional impact and meaning than just mere representations.

Photography offered a medium that could document immediate action. In this way, it was used to record historical events and provided a beginning for the idea of photo journalism. In fact, the Civil War became highly documented by early photographers and presented a stark and often brutal representation of combat deaths.

So how does photography’s often controversial past and development through the centuries affect our perception of it today? I remember one of my college art history students coming up to me after class and telling me about her experience at a gallery who refused to exhibit photographs because they only displayed “real art.” Is this just a random incident or do you think that this past bias against photography still exists? Please share your comments and experiences with us below.